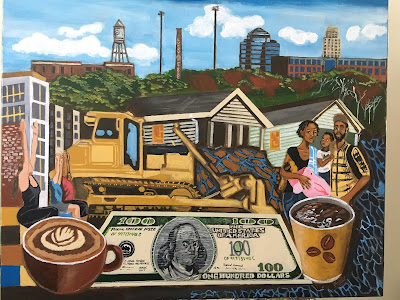

There are stories that relate both the good and the bad regarding

gentrification. Some talk about the reduction of crime and fine dining and

coffee shops in those buildings that were eyesores before the growth. Others

talk about skyrocketing housing cost and the changing demographics. Where did

the black folks go?

As municipalities grapple with ways to place their arms

around how to discuss what it all means - it’s too much to hug when our arms

are too short.

Capturing the essence of gentrification requires more than

an analysis of current public policy statements. I mean, it’s easy to blame the

boom of inner city growth on corporate entities fueled by greed and an

obsession to dismantle communities. Getting at if that’s fact or fiction

complicates the conversation. Hindsight is 20/20, but can we assume a plot that

imagined all of this?

That too is up for debate.

There are a few givens. Maybe, just maybe, it’s best to

start the conversation with what we know to be true. Again, some will dispute

the truth of my suppositions.

Like some say in their relationship status, it’s

complicated.

A reflection of white

privilege

Here we go.

There’s always danger when a person uses those two words in

the same sentence – white and privilege. It’s one among the many phrases

(systemic racism being another) used to indicate the advantages that come with

being white. It’s perceived as an attack, but these statements are meant to

move things forward in ways that make for a happy union.

Who remembers those good ole days?

White people hate it when black people explain things

related to race (is blacksplaing a thing). Yes, this is a heated discussion accompanied

with “what you mean I got privilege when I was born poor down in rural

Mississippi?” In other words, “I got mine, and don’t blame me”.

But, that’s not the point. What is the point when I assert

gentrification reflects what it means to function with white privilege? It

conveys the power of naming worth and marketability.

A community labeled as blight becomes a gold mine when given

the sanction of white people. Their approval of worth radically shifts the

value of property. These communities are no longer quantified as havens of

massive poverty, prostitution and drug related problems. Once named as diamonds

in the rough, they become hotspots for hipsters willing to transform these

communities into those shinny diamonds.

The power of their privilege is in making their dreams come

true. Their very presence is enough to convince others to make the journey into

the land oozing with potential. The power of white privilege is in their

numbers. Being there is enough to attract others.

“If Becky and Harvey say it’s safe, it must be safe. Right?”

But, there’s more.

A reminder of

systemic racism

Getting to the what requires considerable reflection on the

how. In other words, how did we get here in the first place?

Let’s begin with my owning the “here we go again”.

Systemic racism is another one of those terms that budges

the rage of some white people. How dare you blame it all on a system, when you

blacks have failed to do your part.

This is where I insert rolling eyes and comments about your

great-granddaddy. But, let’s press forward.

As much as we hate pondering the implications of history,

how we got here is critical in fully understanding why and how gentrification

is a burden rooted in historical and systemic racism. It is part of an ongoing

practice of public policies that hinder the advances of black families. It

echoes the manufacturing of policies aimed at maneuvering the placement of

black bodies to extend profit for white people.

Be it government policies that denied black soldiers GI

Bills after serving in the military, public policies that redlined areas

acceptable for blacks to live, the construction of black ghettos to cage black

folks into manageable areas for law enforcement to sustain a system of systemic

poverty, urban renewal projects that eradicated black business districts across

the nation or the exodus that drew masses of white people to suburban

communities after the integration of public schools – housing in America has

been used, both historically and today, to foster systems used to maintain

systemic racism and economic disparity.

Gentrification continues the American legacy of moving black

bodes to benefit space utilized to profit white business interest. Regardless

of the intent and motivation, understanding gentrification necessitates an

evaluation that reflects the history and context of housing trends in

manifesting the power of white privilege and systemic racism.

Undoing the stigma of

ghetto

Now comes the tough part. Like I said, this is tough work

that requires more than a causal glare.

As much as this is about white privilege and systemic

racism, it is also about how we name space. Historically, black space is demonized

in ways that signify unwelcoming environments to be avoided. The perception of

space to escape is displayed as part of the lore of black America.

The ghetto is the escape of “moving on up” for the “Jefferson’s”

and the dream of the characters in “Good Times”. The movement away from black

space, into the world of white America, is the evidence of making it. The

movement out is proof of success beyond the restrictive play of ghetto life.

The “ghetto” is a place of confinement under strict

regulations and restrictions. These are quarters of overcrowded housing and

extreme poverty. These are places where the justice system has a different set

of rules to limit movement among those grappling to find ways to break free.

Notwithstanding the terms used to define these communities,

the virtues related to living in “the hood” outweigh the categorization of

those who call it home. The naming of the public persona of the boys and girls

who live in the hood is a matter that deserves critical critique beyond the

negative nuances that shape how people think.

But, this is a discussion about gentrification. Getting to

the now involves how the power of white privilege is used to undo the stigma

regarding life in the perceived “ghetto”. This is about the renaming of black

space. This is about undoing the shame of life in space carved out and redlined

to advance an agenda aimed at protecting the interest of white people. This is

about changing the rhetoric involving black space as part of a public policy

agenda.

Thus, this is, in some ways, about the construction of terms

to undermine black space to foster policies to police and incarcerate black men

and women. This is about demonizing areas, and the people who live there, to regulate

their movement.

What you trying to

say?

I’m glad you asked.

The questions and solutions related to gentrification go

much deeper than many assume. Like most of what fractures America, it all comes

back to America’s unwillingness to concede how race and racism shows up in

practices and public policies that support systemic racism.

There he goes again, blaming it all on racism.

Sorry, but a casual study of American history brings us back

to the core of all our problems.

The devil didn’t do it. Racism got us here.

Well, that is the devil, isn’t it?

What should we do in Durham to prevent displacement? I think that's an important goal, but I haven't heard any realistic proposals to stop it, and hope is not a strategy. The "missing middle" initiative of the planning department is going to make things worse, with the only winners being developers who are eager to have the backing of city government to buy small houses, knock them down, and build high(er) end duplexes. Their argument starts out about affordable housing, but ends up amounting to, "we have a lot of people moving here from Boston and San Francisco, and they may want an array of choices instead of just an apartment downtown. They may want to have a yard. Having duplexes where houses currently are located would help more people have yards."

ReplyDelete