Some

call it Southern pride. Others call it racism. Maybe the truth is somewhere in

the middle, making it difficult to understand the difference.

I

began my day in search of the truth. I should have known it would be a bad day.

It

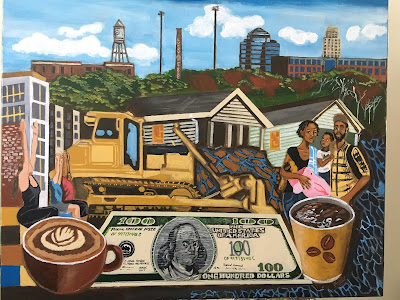

started with a cup of coffee at H&W Drug Company, a locally owned business

with an old school lunch counter. I paid one dollar for the cup and left the

same for the tip. The people lined up next to me updated each other on life in

Newton, NC. It was part yes ma’am and a bunch of Southern hospitality that made

Newton the perfect place for the people at the counter to live.

My

cell phone buzzed, alerting me of a text message.

“Aretha

just died.”

We

knew it was coming, but it still hurt. I looked at the people at the counter to

share the news.

“Aretha

just died,” they looked at me in dismay. I repeated. No change.

“Queen

of Soul,” I said. They looked at me in a way that said “what?”

They

don’t Know Aretha Franklin.

Maybe

they don’t listen to black music, I thought as I prepared to leave. I was

reminded of my first day in Newton. I ordered breakfast at Callahan’s, a diner

on the other side of the town square. I was surrounded by pictures of John

Wayne, the godfather of American Western movies.

Wayne’s

quote, in the May 1971 issue of Playboy, was stuck in my head in a way that

felt like a scene from the movie “Get Out”.

“With

a lot of blacks, there’s quite a bit of resentment along with their dissent,

and possibly rightfully so. But we can’t all of a sudden get down on our knees

and turn everything over to the leadership of the blacks,” Wayne said. “I

believe in white supremacy until the blacks are educated to a point of

responsibility. I don’t believe in giving authority and positions of leadership

and judgment to irresponsible people.”

The

pictures felt like a public service announcement - black folks, stay in your

proper place, or we’ll meet you on the other side of the O.K Corral when the

sun goes down.

It

was shortly before 11:00 a.m., and the crowd was gathering for the Solider

Reunion parade. That’s what the people in Catawba County, NC call this brand of

intimidation. The book “Looking Back, Marching Forward: One Hundred Years of

Solider Reunion, published by the Catawba County Historical Association, dates the

event to 1889. That’s when Julian S Carr published a resolution in the News and Observer to form the

Confederate Veterans’ Association of North Carolina.

In

addition to forming the state organization, groups were asked to send delegates

to the National United Confederate Veterans convention to be held in 1890. By

1903, the planning of reunions came under the auspices of the United Daughters

of the Confederacy.

Newton’s

version of Southern pride is deeply entrenched in the culture of the Soldiers

Reunion. Children walked around the square holding their parent’s hands with

Confederate flag stickers on their garments. Trucks with Confederate flags in

the back lined up for the parade.

The

time before the parade evoked the type of symbols that bruise the souls of black

people. I walked through the crowd suspicious that two men wanted to have a

conversation regarding why I was there, and it being better for me to go back

to where I came from.

The

tension was deeper than the pretension that normalized the moment.

“Black

Confederate Soliders Salute Thomas Stonewall Jackson and Nathan Bedford

Forrest,” are the words on a banner at a booth promoting black love for the

Confederacy. “It has been estimated that over 65,000 Southern blacks were in

the Confederate army ranks. Over 13,000 of these ‘saw the elephant’ also known

as engaging the enemy in combat.”

I

couldn’t help but think “did slaves have a choice?” I few men, wearing leather

jackets with Confederate flags emblems on the back, seemed to dare me to refute

the message on the banner. I kept walking knowing the fake news wins, and black

lives don’t matter when the crowd is swayed in support of this version of

Southern pride.

I

stood in the shadow of the 26-foot Confederate monument erected to remind

people the war continues. Everything

about the statue felt like a middle finger to the demands of the Union army. In

the South, the Confederacy didn’t end with the Civil War. Statues were

dedicated commemorating the ongoing quest for white supremacy.

The

statute in Newton, NC was dedicated during the 1907 Solider Reunion

festivities. The widow of Stonewall Jackson declined an invitation to attend

the event, citing poor health. Jack and Warren Christian, the great-great

grandsons of Stonewall Jackson, wrote a letter, published in Slate Magazine on

August 17, 2017, requesting the removal of Confederate monuments because they

consider them racist.

“We

have learned about his (Stonewall Jackson) reluctance to fight and his teaching

of Sunday School to enslaved peoples in Lexington, Virginia, a potentially

criminal activity at the time,” the great-great grandsons wrote. “But we cannot

ignore his decision to own slaves, his decision to go to war for the

Confederacy, and, ultimately, the fact that he was a white man fighting on the

side of white supremacy.”

That’s

not how Southerners felt when they dedicated the monument in Newton. Between

15,000 to 20,000 people attended the unveiling of the monument. No one showed

up to protest the monument based on how it made black citizens feel. There was

a group who protested due to the removal of a tree. The tree mattered more than

how black people felt.

Julian

S. Carr played an instrumental role in bestowing white supremacy and the rise

of the Klu Klux Klan, in North Carolina. He called the murder of 60 blacks

during the Wilmington Massacre of 1898 a “grand and glorious event.” Carr

celebrated violence and the lynchings of blacks. His popularity in North

Carolina was enough to land him a nomination to become vice President of the

United States at the 1900 Democratic National Convention.

The

Confederate soldiers “saved the very life of the Anglo Saxon race in the

South,” Carr said during the dedication of Silent Sam, the Civil War Monument

on the campus of the University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill, in 1913. “The

purest strain of the Anglo Saxon is to be found in the 13 Southern States.”

Carr

ended his speech with a story about how "the purest strain of the Anglo

Saxon is to be found in the 13 Southern States," after which he ended his

speech with a personal story about how he "horse-whipped a negro wench

until her skirts hung in shreds" after the war in the presence of 100

Union soldiers.

When

protestors toppled Silent Sam on August 20, it was perceived, by some, as an

attack on Southern pride and heritage. Like the 26-foot high monument in

Newton, NC, Silent Sam is a symbol of intimidation. It is a reminder that the

attack on black people didn’t end with the Civil War. The Confederacy never

died. The Soldiers Reunion reclaims the goals of the men and women who fought

to assert the claims of white supremacy.

The

signs of Southern heritage and white supremacy merged to form a new collective

identity. Absent was the suppression of images that are often assumed to

promote racism. They were in full display. It felt like racism has come out

from hiding. It felt like hate unencumbered by how it makes black people feel.

They didn’t care that I was watching. They seemed to gloat in their ability to

wave Confederate flags. It felt like an entire community was spitting in my

face.

The

parade started at 4:30 p.m.

Confederate

soldiers packed the streets. Six men pointed their rifles upward and fired

shots in the air. Women dressed like Southern Bells walk ahead of a truck

loaded with Confederate flags. The long line of jeeps, trucks and cars hoisting

the “Blood Stained Banner”, the national flag of the Confederacy, was more

than any black person can take.

The

last of the cluster of flags passed where I was standing. I took note of the

line of people on both sides of the street. Men, women and children flapped

Confederate flags to conjure the spirit of the moment – white power, white

supremacy and white solidarity. My disappointment in the celebration paled in

comparison in what was missing.

Where

is Black Lives Matter? Where are the chants of “no justice, no peace?” Where is

the crowd of progressive white people to fight the assumption of hate? Where

are local black citizens to protest the mob displaying the symbol of white

rage?

“Excuse

me sir,” I middle-aged white woman said as she approached. “May I ask you a

question. How did that make you feel?”

I

hesitated.

‘I

don’t know,” I answered. “I have many thoughts.”

“I’m

from Newton. I’ve been coming to this event since I was a kid. It has never

been this bad. It was too much. It’s too much for me. I just wonder how it made

you feel.”

I

paused to acknowledge the brewing of tears.

“I’m

finding it hard not to cry. I. I…”

“I

know,” she touched my shoulder. “I know. Me too.”

There

was something about the look on her face. It was too much for her to take. We

both fought back the tears. My attempt didn’t last long. It was the thoughts

about my ancestors. A part of their fear was captured in that moment. The

flags. The cheering crowd and 26-foot statute to celebrate the Confederacy – it

was too much to hold without the flooding of tears.

I

nodded my head to denote my appreciation. She did the same.

I

watched as the parade continued. One by one, face by face, thought by thought,

it was too much to limit to a few words. The history was not enough to explain

that moment. The pictures of John Wayne on the wall at Callahan’s told part of

the story. None of it is enough to explain the rest.

They

didn’t know Aretha Franklin. I took a few deep breaths before leaving.

James

Baldwin said it long ago. “Nobody knows my name.”